In a recent Intellectual Property Enterprise Court (IPEC) decision – Battlekart Europe SA -v- Chaos Karts 1 Limited & Ors [2025] EWHC 1936 (IPEC) – the court was once again required to decide on the validity of a patent over alleged ‘prior uses’.

It has been a few years since the last key decision on the law regarding prior use, being Claydon Yield-O-Meter Limited v Mzuri Limited [2021] EWHC 1007 (IPEC) , where we represented the successful defendant. You can read our blog on this decision here.

This new judgment confirms the rules that are to apply when considering invalidity of a patent for prior use.

The law

The starting point is that a ground for revocation of a patent is that the invention is not a patentable invention (s.72(1)(a) Patents Act 77 (“PA”)). When considering a patent compared to a piece of prior art or prior disclosure, a patent may be granted only where “the invention is new” and “it involves an inventive step” (s1PA).

“An invention shall be taken to be new if it does not form part of the state of the art” (S2(1) PA), and “an invention shall be taken to involve an inventive step if it is not obvious to a person skilled in the art, having regard to any matter which forms part of the state of the art”.

The question therefore turns to what is in “the state of the art”. This includes all matter which has been “made available to the public” anywhere in the world before the priority date (S2(2) PA).

The question in the case of prior use is therefore what was disclosed by way of that prior use, and then whether the patented invention was disclosed by that prior use (i.e. not new) or was it obvious to a person skilled in the art over that disclosure (i.e. not involving an inventive step).

HHJ Hacon reaffirmed the approach taken in the Mzuri case, and quoted the following principles from that judgment:

- [72] It was common ground in this case that in a prior user case in which it is said that the invention was made available to the public, even though nobody in fact took advantage of that availability, the information made available is that which would have been either noticed or inferred by a person skilled in the art who, hypothetically, had taken advantage of the access to the invention established on the evidence. I agree. In effect, the hypothesis concerns a skilled person as observer.

- [73] Mr Nicholson made the further point that for the invention to be enabled, the skilled person need only have been able to discern details of the invention at the level of generality at which they appear in the claim. I agree.

- [74] As appears from Folding Attic Stairs [Folding Attic Stairs Ltd v Loft Stairs Co Ltd [2009] EWHC 1221 (Pat)] it must be assumed that the skilled person’s access was limited to that permitted in law; access by trespassing, for instance, is excluded from the hypothesis.

[Our team also represented the Defendant in the Folding Attic Stairs case.]

The patent in play

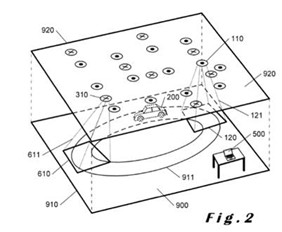

The patent in this case was for a system for creating an immersive multi-player experience which combines driving a real go-kart with the features of a video game like Mario Kart. The driving track is projected onto the floor, and obstacles are projected onto that track in a simulated ‘extended reality’ experience – complete with banana skins making the kart spin around if driven over.

Figure 2 shows an embodiment of the invention:

The prior uses

The judgment analyses two separate alleged prior uses of this invention, before the patent’s priority date (and so forming part of the state of the art).

- The Battlekart Disclosure: a demonstration by the patentee of the Battlekart system conducted in Mons, Belgium before the priority date.

- The MIT Disclosure: a demonstration of a radio-controlled toy game based on Mario Kart created by three students at MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology).

The decision on validity over the prior uses

The Battlekart Disclosure

When deciding what was disclosed by this demonstration, the judge found that it was that which a member of the public attending the event in Mons could have seen, by the naked eye. The defendants relied on five videos shot on various dates to evidence what an attendee would have seen.

The elements of the patent that would not have been disclosed to the skilled person/team by this prior use were:

- the tracking system,

- at least two electromagnetic emitters on the kart one of which must be an infra-red emitter and

- a sensor with a camera capable of detecting infra-red radiation

The question then becomes whether these elements of the patent claim were obvious over what was disclosed.

The judge found that a skilled team which had attended the Battlekart Disclosure would have thought it obvious at the priority date to use an existing and known tracking system that uses IR transmitters as a tool to create an improved karting experience something like the one presented by Battlekart. The judge then found that once this decision had been made, choosing to have two or three IR LEDs on the karts would have been a readily available and obvious option.

The claim of the patent therefore was found to be invalid as it lacked an inventive step over the Battlekart Disclosure.

The MIT Disclosure

When deciding what was disclosed by this demonstration, the judge found that it was that which would have been seen by the skilled team on a hypothetical visit to watch the students’ game in action. The nature of that information was inferred from a report written by one of the students and from what can be seen in one of his videos of the game.

The MIT game used small toy karts the size of ‘Matchbox’ toy cars, and so the part of the invention that was argued to not have been disclosed here was the presence of a ‘kart’ at all.

The question to be determined was therefore whether the skilled team would have found it obvious to scale up the MIT game to a full-size cart system as claimed.

The judge found that the claim lacked inventive step over the MIT Disclosure despite this difference, finding in particular the evidence that the patentee’s own project started with a prototype of a size something like the MIT game and that it had been scaled up using the known tracking system as convincing.

Comment and practical tips

Prior use decisions are sometimes seen as harsh, but here the patent was also found to lack inventive step over an earlier patent application filed by Disney and for added matter. Therefore, it seems to be a doomed defence of the patent from the start, but the application of prior use will be of interest to inventors and their patent attorneys when advising on both patentability of a system that has already been tested or disclosed and how and where to undertake such testing before filing their applications.

For inventors:

- The safest thing to do is to not test your invention anywhere in public prior to the priority date – or even near to somewhere with public access, for example a footpath across private land as in the Mzuri case. Here, had the inventor only demonstrated the system to its internal team and legal advisers before filing the patent, then the Battlekart Disclosure would not have formed part of the state of the art to use in a validity attack.

- Ensure terms of confidentiality are imposed on those who are present during testing – here the judgment notes that there was no confidential, contractual or other restriction placed on anyone who was passing by the MIT Disclosure (albeit this was a disclosure of a similar system by a team other than the patentee, so it was out of the patentee’s control).

- When testing an invention, make sure you discuss and document any steps taken (or that you would have taken) to prevent a public disclosure. The more detailed this is, the more likely you would be able to convince a judge that there was no public disclosure.

And for those challengers to the validity of a patent:

- See if you can find any evidence or indication that an invention has been tested or otherwise disclosed prior to the patent’s priority date, and if so investigate where and how such testing took place.

- Compiling a series of documents and videos can help the court to determine what would have been disclosed to an attendee viewing the disclosure, as the Defendant did successfully in this case.

- It is not just the patentee’s own disclosures that are potentially relevant prior uses, as here the MIT Disclosure also formed a successful invalidity attack.

- If you are seeking to rely on the observer having equipment to assist with the observation, such as binoculars, a video camera or a drone, then evidence may be needed as to why that person could reasonably have been expected to carry that equipment at the time (as discussed in the Mzuri case).

- Ensure that the disclosure really is public and that access to the area from which the disclosure may be seen is permitted in law, as the Mzuri judgment is clear to exclude disclosures where there is only access by trespassing, for example.

We’re here to help

If you’re thinking about enforcing a patent, or facing a patent dispute, don’t let ‘prior use’ catch you out. Speak to our intellectual property team for clear, commercial advice on enforcing and defending your innovations. Our IP team has acted on the key cases establishing the law in this area.